Everyday Oil: Energy Infrastructures and Places That Have Yet to Become Strange

BY ANNE PASEK

About This Project Edmonton is the industrial and policy base for much of the oil sands development in the north of the province—spectacularized through the tar sands campaign, and now the subject of bitter political and cultural divides within the province. I recently returned to this city, in large part, to study these conflicts and the rhetorical lines that hold Alberta’s relations to oil—tenuously—in place. And yet, I found that oil surfaced in so many parts of my everyday life in Edmonton, forming an underacknowledged foundation to institutions and imaginaries big and small.

This project is an attempt to observe some of these moments of everyday oil as both an insider and outsider to this place. It is intended, as Kathleen Stewart writes, as an experiment more than a judgement. Drawing from experience, photos, and memory has let me linger longer in the everyday, in the ordinary, and the stories and spaces that compose a city and the lives lived therein. It is a partial mode, but such is the experience of experience.

I share this with you in the hopes that you might also sense oil in your everyday, in Edmonton or in all the other places in the world that have, to varying degrees, oil in their foundations.

JASPER AVE.There are six lanes of traffic on this road, I complain to a friend. It’s practically a highway. They blink incredulously at the comment.

The street connects downtown Edmonton to the boutiques and cafes of 124th Street. Lined with glass condos and restaurants, it tallies up to as close a picture of dense urbanism as you’ll find in this city. People even go pub crawling along the avenue.

Across six lanes of traffic? Of course.

THE MACKENZIE RIVER PIPELINEA narrow pipe cuts across the canopy of the ravine, visible only from the gravel path below. I can’t find any mention of it on city gas maps, nor does its size suggest much of substance. Nevertheless, it was a captivating mystery as a child, primarily because of its proximity to an abandoned fallout shelter built in the riverbank above. How many of us could have possibly entered in the case of some cataclysmic event? And what would the pipe deliver in our time of need: air, water, or fuel?

ENBRIDGE CENTREI find myself in this glass office tower—unexpectedly—as part of a Wet'suwet'en solidarity protest. Fifty of us, a mix of settlers and Indigenous youth in regalia, first mustered in a mall blocks away. The city centre’s network of pedways, designed to keep shoppers out of the cold, also insulated us from any locked doors or security guards that might meet us on the streets below.

Our target was not the building’s titular energy company, but a Bank of Montreal branch newly installed on the main floor. We occupied the lobby for a few hours of drumming, improvised speeches, and song. Employees skirted awkwardly around us without making eye contact, their discomfort palpable (but not, seemingly, unmanageable).

PIPELINE PATHWAYSA trail divides a neighbourhood and an industrial park, running as flat and straight as the pipelines buried beside it. Battered plastic flags in the grass tell the hidden story: yellow for oil and gas; red for electrical; orange for ICT.

So much of the city’s green spaces are squeezed into these linear parks, scraps spared from commercial development in order to keep shovels away and insurance rates low. Yet these spaces don’t so much function as parks as they do roads without cars. Dog walkers, cyclists, and runners all pass along here, but never linger long. I’m grateful that these paths afford some measure of alternative mobility in a city made for cars, yet I’m never quite at ease inside them. Instead I’m focused on the horizon, shoulders tight, rushing forward like the gas underneath my feet.

THE DERRICK CLUBA rich high school friend was once my ticket into this private club, founded by a group of oil men in the 1950s for their leisure. Past the gate we would swim, play in the arcade, and eat countless french fries, all charged to the family account. Everything and everyone else were met with teenage ennui. A minor scandal, fixed in our minds, lay in the rumoured disparities between the men’s and women’s changing rooms: the former was apparently much larger and contained a sauna.

Investigating seems impossible now; the friendship is lost and the club is not accepting new members at this time.

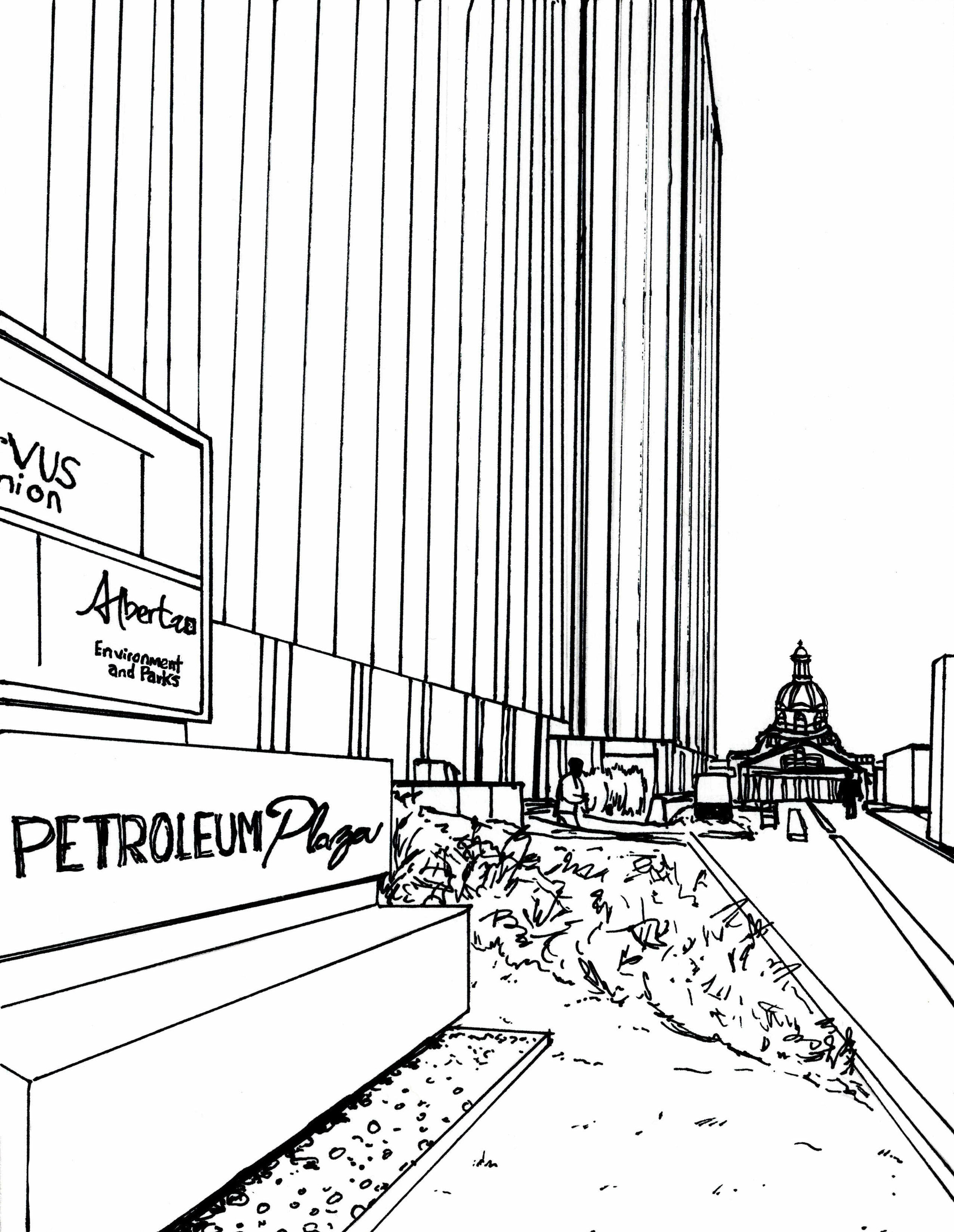

PETROLEUM PLAZAI notice the name of the building only after I arrive at the credit union branch. I explain that I’m here to move all my accounts out of my old bank, which invested heavily in fossil fuels. The credit union employee smiles nervously and tells me that, this being Alberta, they also have their ties to the patch. They do have one ‘ethical’ fund, though that manager is only in on Thursdays.

Outside, the plaza neatly frames the legislature building down the hill, as if I needed a further reminder.

TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PIPELINE

They’ve been laying pipe along the city’s ring road for months, moving dirt and machines up and down the corridor they set aside for projects like this when they first built the highway. You might easily confuse it for the construction work underway to widen the highway itself, if not for the shiny, blue-green cylinders of metal stacked next to the trenches.

When they first broke ground, less than half of the permits for the pipeline route were secured. Many are still uncertain—blockades, protests, and land defenders have and will continue to resist neat lines drawn on maps. Billions of federal dollars were needed to prop up its promise, to keep the project alive. Negative oil prices and a global pandemic threaten to erode whatever foothold that investment won. Yet here on the highway, across moments of gridlock and speed, the pipeline already exists, sunken into the earth and into the everyday.

Inspirations for This Project Hern, Matt, Am Johal, and Joe Sacco. Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life: A Tar Sands Tale. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

Goldring, Hugh, and Nicole Marie Burton. The Beast: Making a Living on a Dying Planet. Edited by Patrick McCurdy. Toronto: Ad Astra Comics, 2018.

Petrocultures Research Group. After Oil. Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta, 2016.

Stewart, Kathleen. Ordinary Affects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Anne Pasek is an interdisciplinary researcher working at the intersections of climate communication, the environmental humanities, and science and technology studies. She studies how carbon becomes communicable in different communities and media forms, to different political and material effects. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Cultural Studies and the School of the Environment at Trent University, as well as a Canada Research Chair in Media, Culture and the Environment.