Tower to Tower

BY HENRIETTE STEINER & KRISTIN VEEL

In May 2020, we published Tower to Tower: Gigantism in Architecture and Digital Culture (MIT Press), a cultural history of gigantism in architecture and digital culture, from the Eiffel Tower to the World Trade Center. We focus on two paradigmatic tower sites: the Eiffel Tower and the Twin Towers of the destroyed World Trade Center (as well as their replacement, the One World Trade Center tower) and consider, among other things, philosophical interpretations of the Eiffel Tower; the design and destruction of the Twin Towers; the architectural debates surrounding the erection of One World Trade Center on the Ground Zero site; and such recent examples of gigantism across architecture and digital culture as Rem Koolhaas's headquarters for China Central TV and the phenomenon of the “tech giant.”

Examining the cultural, architectural, and media history of these towers, we analyze the changing conceptions of the gigantism that they represent, not just as physical structures but as sites for the projection of cultural ideas and ideals. We bring together theoretical reflections and critical engagements with canonical and contemporary cultural and architectural theory. Furthermore, we call on our own situated experiences and observations, in particular with regard to the One World Trade Center. In addition, we triangulate the discussions in the chapters with two other strands. One of them is a series of short prologues at the beginning of each chapter, including the Introduction and an Epilogue at the end of the book. The prologues strike a different, more embodied and poetic tone than the traditional scholarly subject position, and they present alternative pathways into our argument. They reflect the difficult and productively incomplete fusion of horizons that the collaborative experience of writing this book has offered, thereby gesturing toward the slippery forms of commonality we discuss.

Writing this book has brought our singular and situated knowledges and experiences into dialogue, and has provided us with a way of working through and beyond the idea of the academic author. In this ongoing dialogue we have found a way of sharing; this sharing has been crucial for us to approach the gigantic objects and phenomena we discuss in the book—phenomena in which we are ourselves implicated, sometimes in uncomfortable ways, and which always implicate us as well as others. Yet, we have also encountered the limits of that sharing, and the prologues, including the discussion of scaffolding in the prologue above, are places where we reflect on those limits. The other strand is nonverbal and consists of a series of drawings by artist Maria Finn, which provide visual reflections on the paradoxes of appearance involved in our discussion of the towers and their gigantism. The drawings have been conceived by Finn in dialogue with our developing manuscript, and have formed important vehicles for our thinking.

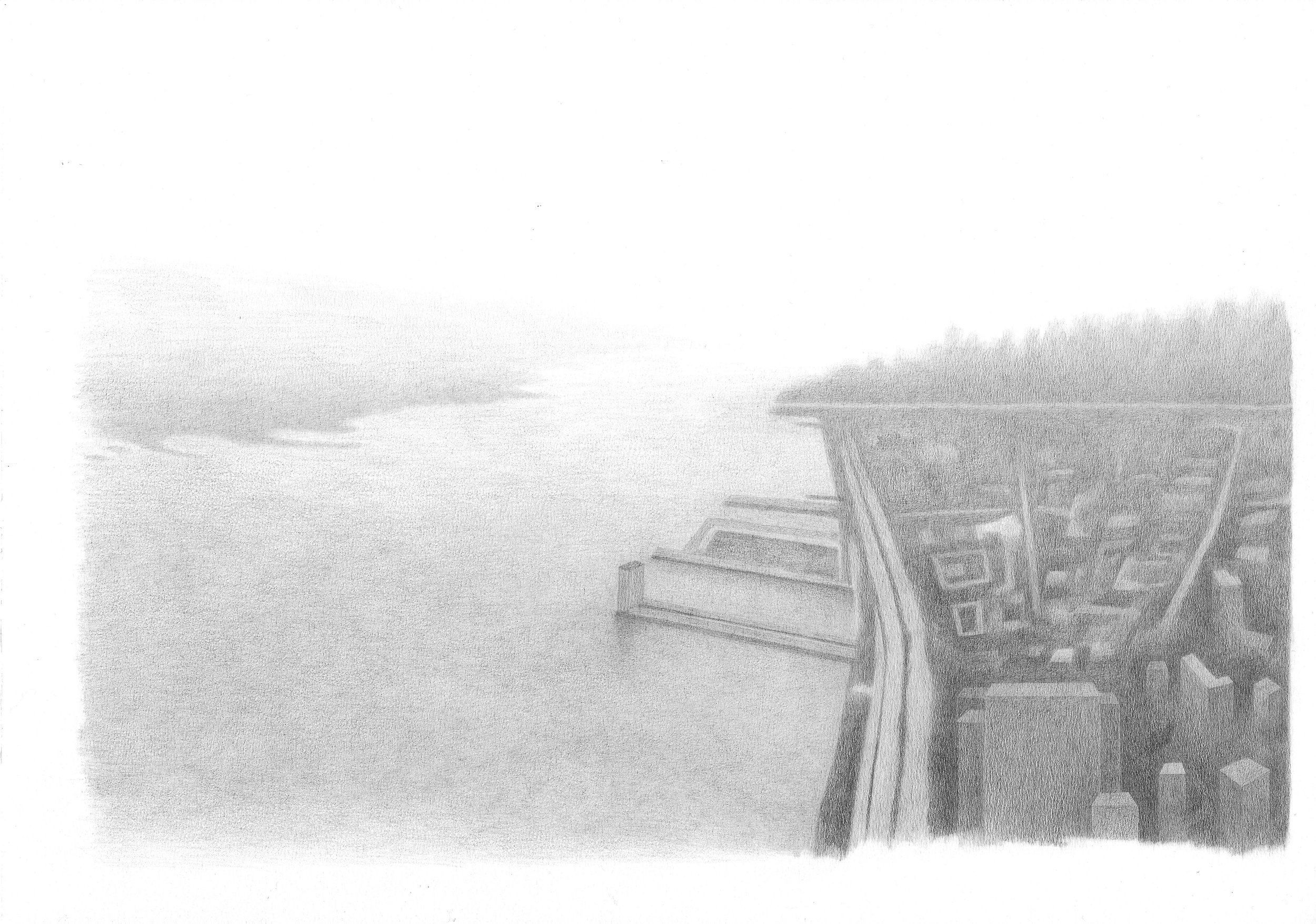

The excerpts below include the slightly edited prologue for the book’s Introduction and for Chapter Three, “The One World Trade Center Observatory: Caught Between Vertical and Horizontal Gigantism.” Two drawings by Maria Finn accompany our text.

Maria Finn, Unfinished #16, pencil on paper, 29 x 42 cm, 2018. © Maria Finn.

Prologue: Scaffolding

Copenhagen, February 2019

When my mother died, I bought a house that needed a new roof. Somehow crisis and construction, eruption and containment, loss and latitude often come as one package, I have found.

Henriette visited me, and I took her to the top of the scaffolding that surrounded the entire house at that point to inspect the construction work. Neither of us were very agile—Henriette seven months pregnant, and I, as always, afraid of heights. We sat on the roof, perhaps six meters above ground, surrounded by scaffolding. We talked about physical scaffolds, emotional ones, and the theoretical scaffolding that we as academics build around the phenomena we want to explore in order to get at eye level with our objects of study.

We had been working together for some time on the changing connotations of transparency and invisibility today. We had received a grant to host a range of conferences; we had brought together scholars from around the globe and from different academic disciplines for discussion; we were editing books and special issues and co-writing a number of articles. Yet although we could see that our ideas had struck a chord, we had trouble finding ways to word exactly what we were looking at, as if the questions themselves needed support, were unsafe and left us vulnerable. I do not recall if this was when the idea for this book first took shape. As I think back today, the idea was definitely latently present that quiet afternoon atop my house stripped of its roof. Depending on one’s perspective, it is an opportunity, a conundrum, or an impasse that the question of how to erect something is somehow silently present in sites of destruction.

Remains of scaffolds have been found in caves in southern France, believed to have supported those who painted the walls with reindeer, aurochs, mammoths, and horses seventeen thousand years ago. In Hong Kong scaffolds of bamboo with nylon string, up to 100 meters high, are not uncommon. In the European Union, the design and erection of scaffolding is regulated to ensure that “the purpose of a working scaffold is to provide a safe place of work with safe access suitable for the work being done.” According to this standard, safety should be independent of the materials of which the scaffold is made.

Yet the standard does not seem to account for theoretical scaffoldings constructed to support arguments and words. While the scaffoldings used in construction work and even emotional scaffoldings, are somehow held in check by the object (or subject) that they support, there is always a danger that theoretical scaffolds might be supporting something that is not really there. That in fact they are creating the gigantic object whose construction they support as they raise us inch by inch above the ground.

The first chapter outlines a theoretical and methodological framework for the investigation carried out in the book Tower to Tower. By moving from the Eiffel Tower to the Twin Towers and then to One World Trade Center and beyond – from one gigantic tower to the next – this book charts gigantism as a significant phenomenon of the present cultural moment and considers its ties to the past. The chapter asks why we should pay attention to gigantism today and suggests how we might go about it. But we also discuss the risk that we become part of the vanishing ontological borderline with which our study of gigantism engages—a borderline that we sense as an entrapment, an uncomfortably sticky position from which to work. So, what kind of balancing act—on a wobbly scaffolding with no railings—do we need to perform if we are to tease out the workings of the latent gigantism in which we are enmeshed?

KV

Wrapped in scaffolding. Photo by author.

Maria Finn, Unfinished # 17, pencil on paper, 29 x 42 cm, 2018. © Maria Finn.

Prologue to Chapter Three, “The One World Trade Center Observatory: Caught Between Vertical and Horizontal Gigantism”

New York, April 2016

The night before I left Copenhagen to meet Kristin in New York City, I dreamed about a future architectural development of Copenhagen. Despite the sprouting of buildings in the twelve-story range in recent years, Copenhageners are known for their ambivalence toward tall buildings. Nonetheless, in the dreamscape, a skyline of fully high-rise architecture was added to the city in a truly spectacular manner. As if I were on an airplane, cruising at low height and looking down on the city, in my dream, the skyline that unfolded before my startled inner gaze was more akin to distant cities like Dubai or Shanghai, collapsing visions of the future onto the Copenhagen I know so well.

Approaching the city from the east, and in fact seeing very little of Copenhagen proper, I first recognized Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava’s actual fifty-story tower, the Turning Torso. The tallest building in Scandinavia, this tower was built in 2005 close to the waterfront of Malmö, Copenhagen’s nearest neighbor on the Swedish coast. In my dream I apprehended Copenhagen in the wide regional sense implied in the 1990s Danish-Swedish political project to create a single urban region across the Øresund Strait. The opening of the Øresund Bridge in 2000 was the most visible infrastructural project supporting this vision; along with it came a railway line ensuring an easy commute across the Strait. However, with the surge of refugees arriving in Sweden in 2015, fifty-eight years of open borders between Denmark and Sweden were terminated, and commuters were suddenly prompted for ID and passports.

Nonetheless, the vision of regional development and joint prosperity for the neighboring countries extends beyond the building of new infrastructure. It includes large swathes of commercial, institutional, and residential architectural development, not least in the southern part of Copenhagen, where an entirely new urban area called Ørestad has been built from scratch since the early 2000s. Ørestad is known for a series of fairly tall and architecturally spectacular buildings, several of which have become world famous, such as the 8 House by Danish architecture firm BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group). Parallel developments have taken place in the smaller city of Malmö, where Calatrava’s landmark tower, so vividly present in my dream, is among the most significant features. The tower was created in the gigantic anthropomorphic image of Calatrava himself, projecting a likeness of the architect’s body as he gently twists his torso toward his own image in a mirror behind him.

However, the visual power of Calatrava’s megalomaniac, notoriously phallic, and very real tower fades in comparison with the lineup of buildings that followed in my dream. As I continued my airborne approach toward Copenhagen, gliding above the water, a series of spectacular new glass-and-steel high-rise buildings appeared on a straight row of islands connected by a superhighway across the Øresund Strait. The footprints of the buildings covered most of these little islands, so that it looked as if the buildings had their feet in the water. The calm blue surface was reflected in the glass fronts of expressive yet geometric buildings with no facades, like the black-box skyscraper one might find in many cities all over the globe today. The climax of this impressive skyline was a gigantic glass-and-steel boxed-in structure in the shape of the Eiffel Tower. So, here it was, in my dream – many times the size of the original. Emitting sparks of glitter. This was the Eiffel Tower’s dramatic and fairy-like twin sister. Highly spectacular, yet only diffusely present. I could not tear my eyes from the structure, infatuated by the very sight of it.

Then a voice invaded my dream: “Mom, are you leaving today?” spoken by an anxious and still half-asleep five-year-old. The words propelled me into the early-morning atmosphere of my dimly lit bedroom, but the image of that fantastic skyline lingered on. A few hours later, when I was on an actual airplane leaving Copenhagen, I looked down on the city and the water from above—just checking in case what I had seen in my dream had magically appeared overnight.

In this chapter we turn to the One World Trade Center, a building that looks as black-boxed as any of the skyscrapers from my dream. We consider this building as we experienced it when we first visited in April 2016 (the trip that commenced with the dreamscape above) – as simultaneously tower, transmitter, and tourist site, as an architectural object and mediated spectacle, and as marked by latent gigantism.

HS

The Turning Torso and Øresund Bridge. Photo by Casper Christensen / David Castor.

[1] BSI, “Temporary Works Equipment: Scaffolds: Performance Requirements and General Design,” standard no. EN 12811-1:2003 (2004).

Henriette Steiner is Associate Professor in the Section for Landscape Architecture and Planning at the University of Copenhagen. She holds a PhD in history and philosophy of architecture from the University of Cambridge, UK, and has been a researcher or visitor at various schools of architecture, including ETH Zurich and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Through her research and teaching, Henriette strives to inspire more self-reflective, diverse, equitable, and compassionate spatial practices for designing cities and landscapes. Henriette is joint project leader (with Svava Riesto) on Women in Danish Architecture 1925–1975, a three-year research project that aims to provide a more just and complete understanding of architecture history by highlighting women’s contributions to the architectural disciplines in Denmark. Her most recent books are co-written with Kristin Veel: Tower to Tower (MIT Press, 2021) and Touch in the Time of Corona (De Gruyter, 2021).

Kristin Veel is Associate Professor at the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen and Research Fellow at the Surveillance Studies Centre, Queen’s University. Her research and teaching focuses on the invisibilities and vulnerabilities that arise with digital technology and datafication and how these may be discerned in film, art, literature as well as in the urban fabric. She is PI of the Uncertain Archives research project that looks at the inherent uncertainties of datafication, and recipient of the Lars Arge Award for Young Scientists 2021. Kristin is coeditor of ten collected volumes and special journal issues, most recently Uncertain Archives: Critical Keywords for Big Data (MIT, 2021) together with Nanna Bonde Thylstrup, Daniela Agostinho, Annie Ring and Catherine D’Ignazio. Her most recent books are co-written with Henriette Steiner: Tower to Tower (MIT Press, 2021) and Touch in the Time of Corona (De Gruyter, 2021).